The “Women in Refrigerators” Trope, Evolved

Written By: Jacqueline Salazar Romo

Date: January 7, 2026

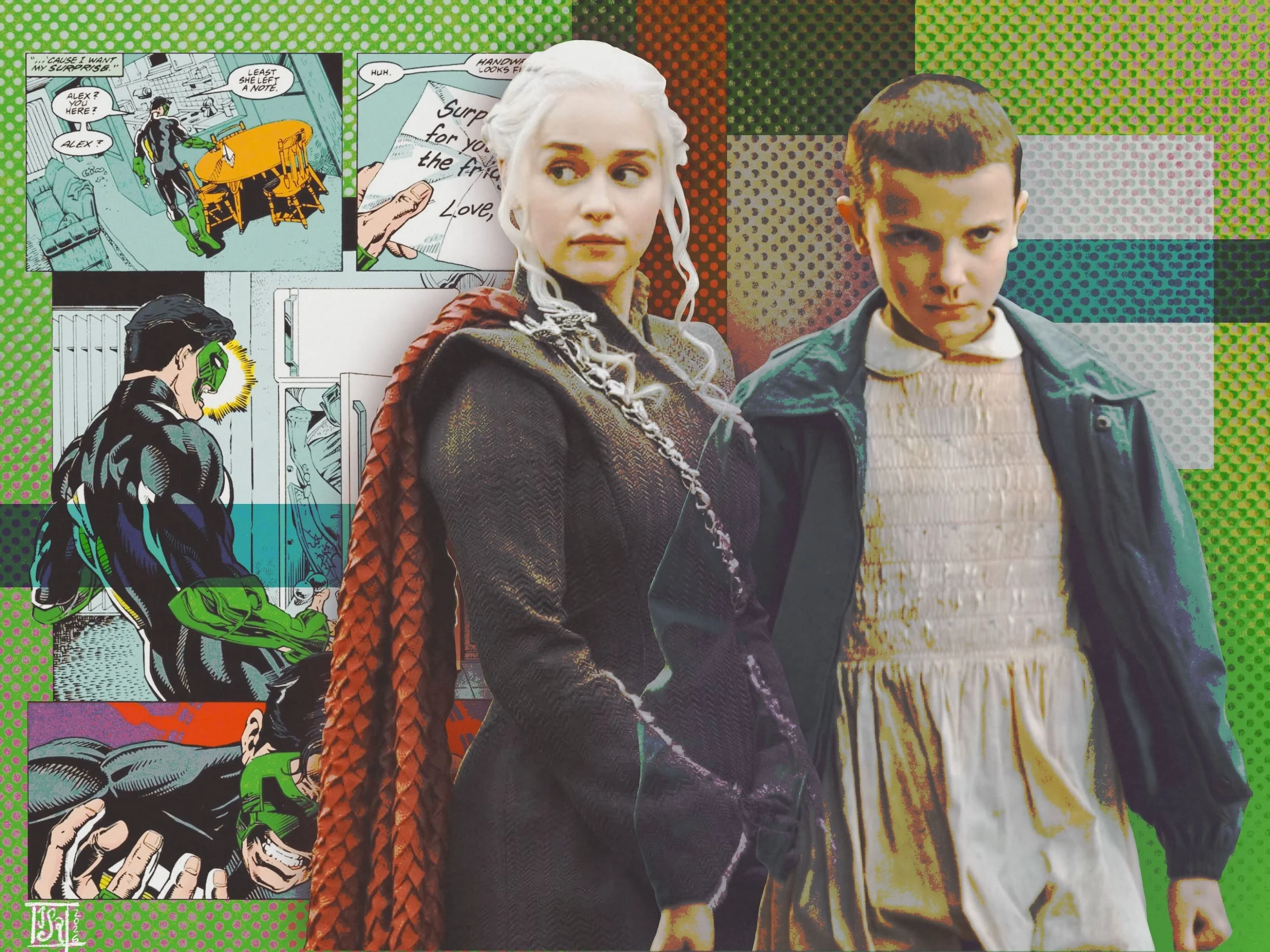

Digital collage by author

*This article contains a range of spoilers for Stranger Things (Netflix), Game of Thrones (HBO), Arcane (Netflix), The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (SONY Pictures), Gladiator (DreamWorks), UP (Disney-Pixar), Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (Lucasfilm), the John Wick saga (Lionsgate), The Legend of Korra (Nickelodeon), and more.

If you have ever been in any literary fiction writing or fandom space, you may be familiar with the term “fridging.” “Fridging” is when a character “exists for the sole purpose of being killed, assaulted, or otherwise harmed in order to serve as an inciting incident that motivates another character’s journey,” as author Fija Callaghan defines for Scribophile. While this trope is tried and true, it seems to be especially prominent when the “fridged” character in question is female. So, let’s talk about the trope and its undeniable bias against women, and how the echoes of this phenomenon have carried on to new storytelling structures.

Origins

The trope was first given a name by author and comics critic Gail Simone, who cites “Forced Entry” (Green Lantern Vol. 3 #54) as a cornerstone of the problematic trend. In this comic, hero Kyle Rayner returns to his apartment only to find that villain Major Force brutally killed his girlfriend, Alexandra DeWitt, and stuffed her body into his refrigerator (“fridging” a character, then, is a very literal and gruesome derivation). One of the most well-known instances of the trope (at least, one of the more familiar and devastating ones for our generation) comes from The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014), in which Emma Stone’s Gwen Stacy dies a tragic and brutal death, with Andrew Garfield’s Spider-Man being helpless to stop it despite his best efforts. It’s easy to find this pattern even outside of the superhero realm: the John Wick saga begins with Keanu Reeves’s titular character losing his wife and having his dog killed, Padme’s death in the Star Wars prequels of the early 2000s triggers Anakin Skywalker’s transformation into Darth Vader, and even further back, classic blockbusters like Gladiator and even Disney-Pixar’s UP also see the heroic male protagonists grieve over their deceased or murdered wives. The trope may have first been pointed out within comic books, but the misogyny behind it shapes more than just that particular genre or medium. It does not matter where you search; you’ll find a dead wife. Ultimately, as Vox puts it, the trope is most pushed upon female characters “to perpetuate the idea that women are objects whose value is dependent on their sexual purity as well as their worth to a man.”

Variations and Evolutions

The concept of “fridging” (and its problematic implications) is not a new phenomenon by any means. NB’s own Rhilynn Horner wrote in great detail here about the adjacent phenomenon of the fetishization of violence against women within the horror genre, and how the “Final Girl” trope often stems from the desire to sexualize and exploit women’s suffering. While “fridging” is not as exclusive to female characters in the way the “Final Girl” trope is, it definitely feels overrepresented and normalized in comparison to male characters (think of all the “dead wife montage” jokes that surface now and again online, for instance, or how common it is for a Disney character to have a dead mother, and of how extremely rarely the genders are flipped for the same to apply to a woman’s “tragic backstory” or motives).

This isn’t to say that there shouldn’t be any storylines in which a character’s arc ends in tragedy; the difference between a good tragic character and a disposable one is how their story is developed. There is also a major difference in how this trope, if ever, presents in a male counterpart. To address this concept, comics editor John Bartol coined the term “Dead Men Defrosting” in response to Gail Simone’s original premise, stating that “when male heroes are killed or altered in such a fashion, they are more typically returned to their status quo in a fashion that women characters aren't.” Whereas male heroes can recapacitate from a great tragedy and come back stronger (for example, The Dark Knight Rises’ Bruce Wayne, played by Christian Bale, who is able to recover from a harrowing match with Bane to fight him again), this same luxury and progression is seldom granted to their opposite-sex counterparts.

When female characters are much more nuanced and multifaceted than the dead wives of yore, their ultimate demise or fall from grace still can feel just as egregious and unfair. Stranger Things’ Eleven, with her ambiguous “death” in the show’s final season, is the latest to join a cast of powerful young women whose ascent into power is often followed by a descent into chaos and tragedy, female characters whose development and ambitions are ultimately thrown out the window for the “plot” to move forward—and by the “plot,” we mean the (usually) male protagonist(s) (and company). Eleven, much like Daenerys Targaryen from Game of Thrones or Jinx from Arcane, is complex, multidimensional, a fan-favorite, and a huge marketable asset (all of these girls are basically the face of their respective franchise). All well-written and fascinating characters, they suffer extensively throughout their arcs through violent and cruel means like abandonment, torture, intense emotional and mental distress, sexual abuse, manipulation, and more. They are easy to sympathize with despite their wrongdoings or flaws, easy to root for and celebrate when it seems that they’ll have the chance to win (whether that win comes from earning a position of leadership or authority, defeating or exerting revenge against those who hurt them, or even just finding normalcy and family, or finding love and domesticity after a lifetime of dehumanization). But then, just as the stakes are the highest they could be and you think they might make it out and finally find happiness, they are written to be killed, to suffer, to sacrifice their aspirations and even their own lives despite everything they have been through.

Here’s the thing: these characters are not direct examples of the “women in refrigerators” trope. They are central to their respective franchises and were written to have depth, as opposed to some of the unfortunate discarded women from earlier years. Conclusively, they are undeniably memorable and beloved. But it’s not their characterization that raises red flags; instead, it’s the concept of ripping everything away from the strong female character that, concerningly, seems to be becoming a trend. The trope and its myriad variations only reinforce one conclusion: women are disposable and most convenient when they are relegated to being plot devices for the benefit or growth of a man; a “good” woman is one who sacrifices for or loses to a man; a woman in power who does not tie her identity and fate to a man needs to be humbled.

Beyond fiction and as silly as it may sound, these trends cumulatively work to construct a deeply misogynistic culture that assigns different values to women, dependent on whether they should be “put in their place” or left to accept objectification and erasure. All the “good” dead or abused women in the examples above sometimes don’t even have names or agency of their own; sometimes, they simply exist in relation to their partner, and their pain and death are merely glorified fodder for said partner’s revenge arc or character development. Inversely, women who are confident and independent are villainized and reviled until they are toned down or made to lose their power and agency (think Korra from The Legend of Korra, for instance, and how her loss of the Avatar spirit Raava, while largely out of her control, causes her to lose her abilities and connection to her mentors). Not only are female characters unjustly burdened with grief and trauma more often, but they also are more likely to bear the brunt of fans’ hatred and vitriol. Following the previous example, Korra is a widely controversial and even unpopular character among male Avatar fans, partially because of her cocky, impulsive, and headstrong nature (attributes that would be celebrated in a male character), and many blame her alone for the loss of the Avatar line. She’s nowhere near the only example, either—almost every time that there is a female character who refuses to get fridged or sidelined, there is an audience that will hate her for having autonomy and perseverance. No matter which way you slice it, there’s always a fridge to stuff a woman into.

Written by: Jacqueline Salazar Romo

About the author: Jacqueline (she/they) is an editorial staff member.

Tags: Misogyny, Literary/Television Tropes, Fridging

Check out our social media for more resources:

Additional Reading

Sources

https://www.scribophile.com/academy/what-is-fridging

https://fanlore.org/wiki/Disposable_Black_Girlfriend

https://www.thecherrypicks.com/stories/in-movies-and-tv-a-good-wife-is-a-dead-wife/

https://www.comicbasics.com/women-in-refrigerators-and-dead-men-defrosting/

https://diaryofacomicbookgoddess.wordpress.com/tag/dead-men-defrosting/

https://usustatesman.com/the-legend-of-korra-isnt-as-bad-as-fans-think/

https://x.com/n4vyist/status/2007207233969631344

https://www.mother.ly/news/why-do-disney-moms-always-die/

Leave a comment